From Gaudí to Bofill

what Catalan architects can teach us about sustainability

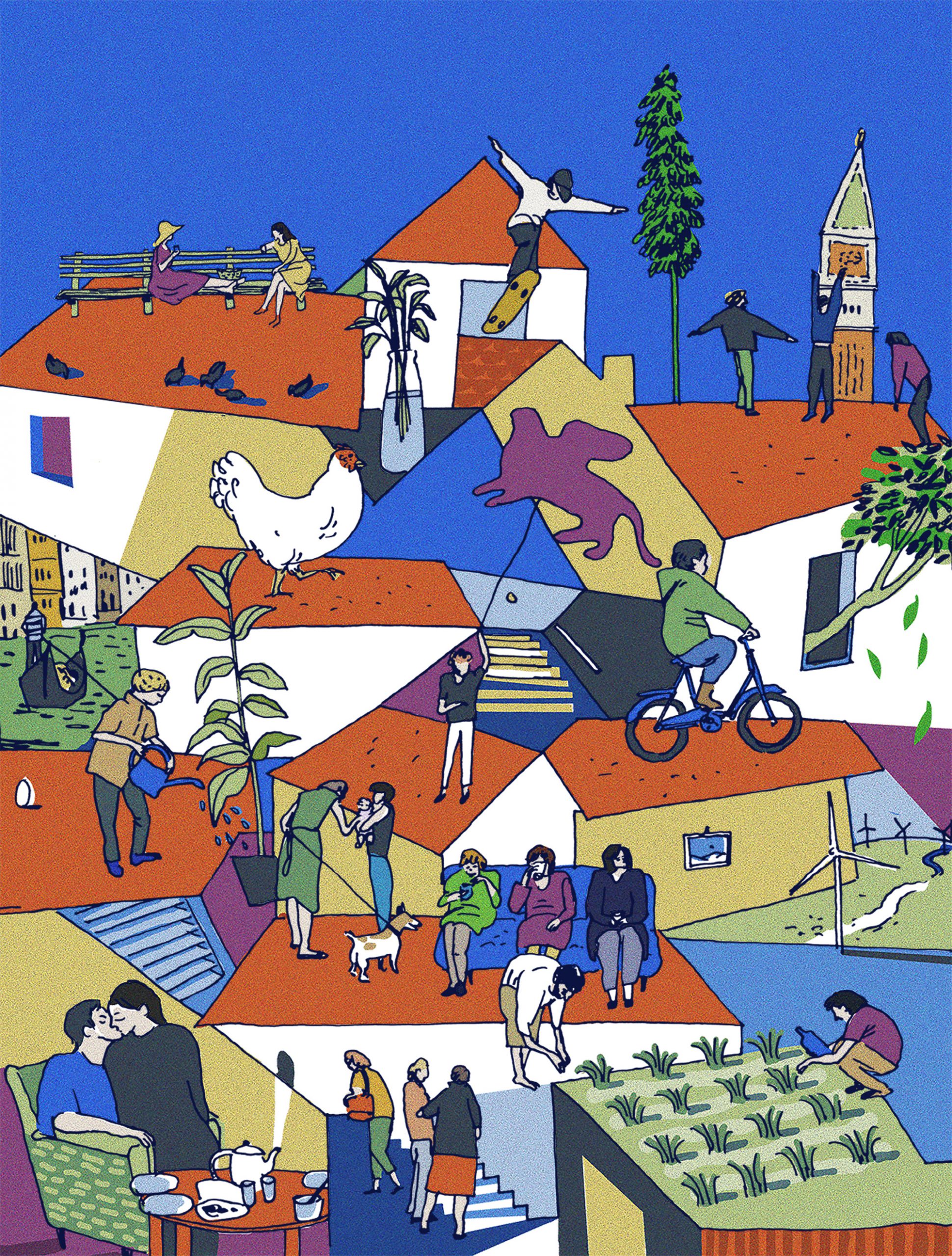

In the last decades, Barcelona has been recognized as a global hub for architecture, urbanism and sustainable building. Catalan architects have a long history of innovation, from Antoni Gaudí’s visionary style to the pioneering works of Ricardo Bofill. We set off on a journey through the Catalan capital to discover the ideas that make the city an extraordinary showcase of urban architecture.

It is not surprising that so many architectural and urban innovation ideas came from this region of 7 million inhabitants. Catalonia is indeed a unique political, cultural and geographical area of Europe with such a diverse landscape: from the picturesque beaches of Costa Brava, to the mountains of the Pyrenees, from traditional fishing villages to the metropolitan district of Barcelona.

Antoni Gaudí, the visionary

In this place, suspended between history and innovation, one of the greatest architects of the last century made his name. Born in 1852, a few kilometres from Tarragona, Antoni Gaudí left his mark more intensely in Barcelona, where many of his masterpieces can be admired: Parc Guell, Casa Battlò, Casa Milà and the Sagrada Familia, to name the most renowned.

Gaudí grew up in an environment defined by a booming population and an expanding industrial development, during which the first Exposicion Universal of Spain took place. It was in this context of ferment that the Catalan architect developed the ground ideas for his future projects.

With his unique style inspired by natural structures, a strongly spiritual vision and a disorientating modernity for his time, Gaudí is recognised as the greatest interpreter of Spanish Art Nouveau, known as Modernism.

But what does Gaudí have to do with sustainability?

Sustainability in Gaudí: nature as a teacher

Although the concept of sustainability did not exist at the time, we can definitely consider Gaudí one of the precursors of this practice for the development of organic techniques and the light, circular approach of his design.

In particular, Gaudí was a pioneer in biomimicry, defined as “the approach to innovation that seeks sustainable solutions to human challenges by emulating nature’s time-tested patterns and strategies.” (1)

For Gaudì, turning to natural ecosystems was not simply a question of fascination or romanticism but an attempt to find answers to practical design issues. He harnessed the natural intelligence to design passive systems in order to reduce the consumption of resources, and build spaces that would do more with less.

When we try to find a solution to our present issues we tend to forget that the Planet runs with a perfectly efficient and regenerative system, where there is no waste and everything is powered by renewable energy. In fact, having benefited from a 3.8 billion year long process of research and development, natural ecosystems would represent the obvious go-to place where to find inspiration and Gaudí was convinced that “the architect of the future will build imitating nature, for it is the most rational, long-lasting, and economical of all methods”.

Biomimicry in Gaudí architecture

Natural principles and organic shapes can be admired in each of the Catalan architect’s masterpieces.

In Casa Battlò we can appreciate an example of bioclimatic architecture. There, Gaudí used a series of passive mechanical air conditioning systems to maintain a stable temperature throughout the year. Along with that he created a multi-story penetrating light shaft that allowed sunlight to filter in from the rooftop skylight, a sign of great awareness of natural lighting principles that are still used in architecture today.

For this project Gaudí decided to transform the existing building instead of demolishing and rebuilding it, as the owner of the building, Josep Batlló i Casanovas, had planned. By renovating the façade and completely redistributing the interior areas the project saved many of the resources required for new construction and, as such, turned out to be a cheaper alternative for the client. In this way Gaudí proved that an environmentally beneficial solution was not incompatible with striking design, but rather stimulated the architect’s creativity and was a delight for the client as well.

Another great example of Gaudí sustainable innovation can be found in the Sagrada Familia. Here, the architect designed the internal structure like a forest, with tree-shaped columns that divide towards the sky like branches. This solution, apart from being astonishingly beautiful, allows the weight of the vaults to be supported without using external flying buttresses, thus reducing the weight and amount of resources needed for the structure.

All the details of the cathedral, which at first glance may seem purely aesthetic, such as the inclination and branching of the columns, or the helical and hyperbolic forms, are in fact the result of a profound study of the architecture and the principles of nature.

Carlos Salas, an engineer for the Community of Madrid and lecturer at the Rey Juan Carlos University and the Polytechnic University of Madrid, explains to Mr. Wynwood that “Gaudí can teach us a lot about how to make architecture more sustainable. His great concern for nature and the environment, together with his creative genius and scientific talent, led him to devise a series of architectural strategies, absolutely innovative at the time, which today can be considered pioneers and forerunners of sustainability in architecture”.

His way of using architecture and design, continues Salas, “have laid the foundations of sustainability in modern architecture, as well as bioclimatic and even biomimetic architecture. Some of these techniques, in fact, were criticised and misunderstood at the time – such as recycling and the reuse of materials – and yet, today, we have realised that they are fundamental to reducing our impact on the planet”.

Ricardo Bofill, between dream and function

If there is one person who has perhaps taken on Gaudí’s legacy more than others, it is a Catalan architect, known for his unique, thought-provoking, forward-looking style, and for creating new perspectives around the role of architecture in society.

There are many words to describe Ricardo Bofill’s architecture: energy and discipline, art and efficiency, creativity and logic. These are apparently contrasting terms and still the Catalan architect has managed to interpret them all in a groundbreaking way during his multi-decade career.

Bofill is considered to be one of the 20th century’s most unique architects and radical visionaries, author of some of the most iconic and classification-defying buildings in Spain: from Walden 7 to Hotel Vela (Sail Hotel), from la Muralla Roja (whose interiors inspired countless movies and series) to the headquarters of his studio-workshop La Fabrica, a repurposed cement factory, which is also the house where the Bofill family lives and represents the built manifesto of RBTA (Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura).

The structure of La Fabrica is an example of the combination between different architectural styles and gives a hint of how Bofill works. It is an idea of architecture that prefers renovation instead of total demolition and that considers the limits imposed by the structure as an opportunity for creativity to thrive.

A local, interdisciplinary approach

Poets, mathematicians, engineers and painters have lived in La Fabrica, and Bofill has always considered them fundamental to maintaining the multidisciplinary approach that characterizes his work.

Having different disciplines dialoguing under the same roof has allowed the architect to discover new methodologies, to remain open to innovative solutions and evolve with the years passing. This open mindedness, the interdisciplinary approach and the organic integration into the surrounding environment are not just key features of his style but demonstrate what sustainability means for Bofill. In a few words: one-size-fits-all solutions don’t work because diversity is the key.

It is a line of reasoning that is in tune with the architect’s vision to keep experimenting when working on a project, learning from the cultural traditions and the climate conditions of the place. Indeed, according to the architect each of his projects should be seen as different parts of a whole, stimulating a discussion of what architecture can do for a place and working locally to respond to global challenges.

As Ricardo E. Bofill (the son of Ricardo Bofill) tells Mr Wynwood, the role of the environment in architecture has changed a lot in the past two decades. Until not so long ago “International Modern Architecture treated natural ecosystems as “dead objects” to decorate sterile spaces. Ecology did not even exist in the vocabulary of architects. The concept of “organic design” has also transformed throughout these last 20 years. Before, it meant copying nature. Now, it means creating living environments, where nature is an essential part of a material palette that helps keep the Planet alive.”

The sector has also become very much aware of its environmental footprint and it’s trying to respond with innovative solutions. “I read that construction is responsible for 20% of yearly carbon emissions” – continues Bofill – “It is frightening. We are in a desperate need to build with net zero impact to the climate. At RBTA Lab we are investigating ways to mix nature in the material equation and optimally be net oxygen positive providers. In this way, cities shall not be the cancers of the Planet but they can be the tropical forests. We need to dream to achieve a required goal, this is exciting work for architects and engineers.”

We must not forget, concludes the architect, that “global warming will still have devastating effects on cities and rural areas around the globe, so we urgently need a planetary conscience revolution. I know it is challenging to be optimistic with current world leaders and conflicts escalating. Nevertheless, I think the revolution has started.”

(1) The Biomimicry Institute. Retrieved February 9th from https://biomimicry.org/what-is-biomimicry/

You may also like

No Man is an Island

No man is an island, but even when he is, and lives happily, it means that he distanced himself from

Circular Cities

Emanuele Bompan is a journalist and geographer. He is the author of the best-selling book “What is

Life on deck

Tommaso Sagnelli, 28 year old Italian takes a life changing decision: quit his job, buy a boat and l

Post a comment