Circular Cities

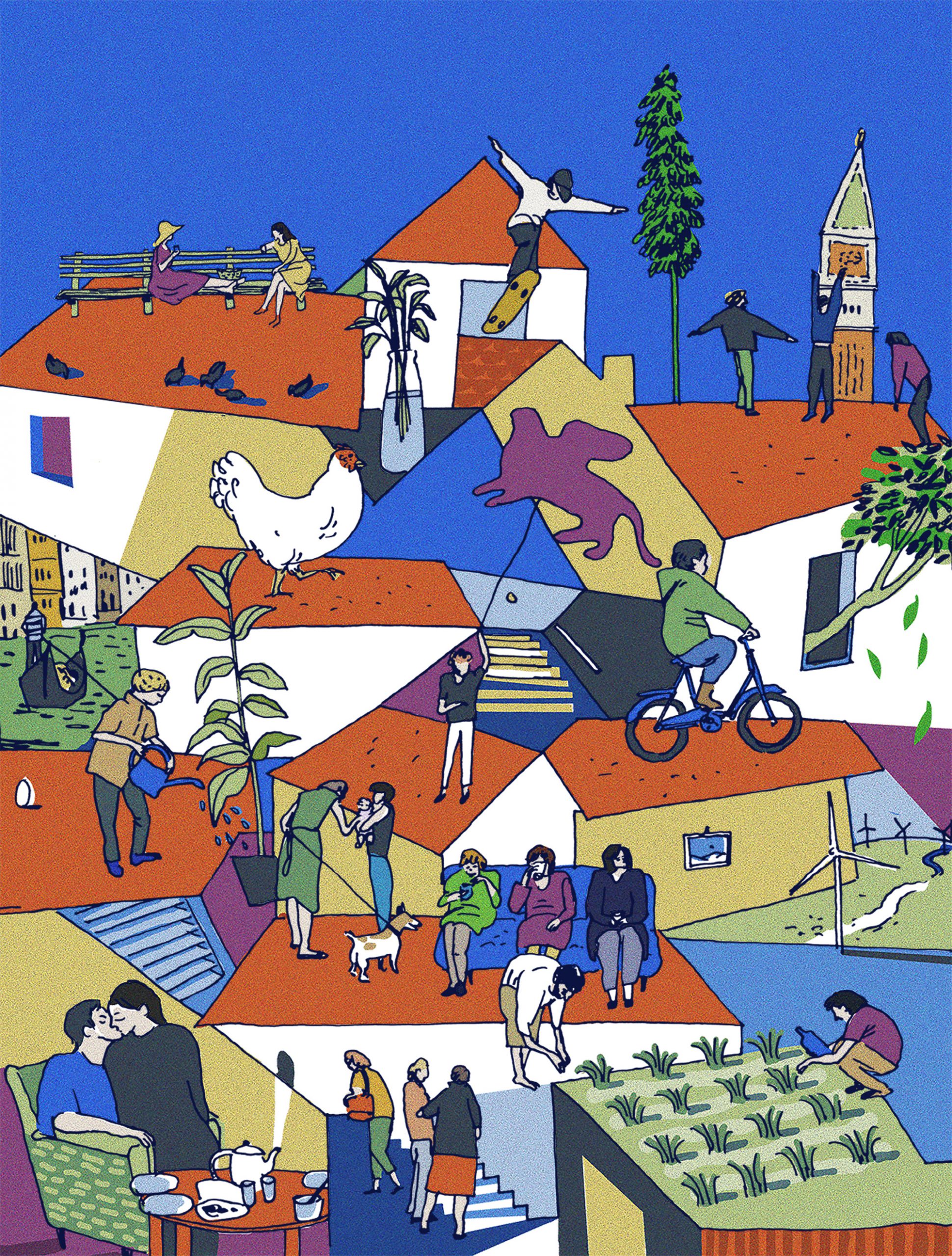

A city is like an organism, made of countless ganglia, networks, spaces, players interacting with each other. Just as a healthy individual has a perfectly functioning metabolism, a healthy city must have an efficient urban metabolism.

A healthy city takes the bare minimum of matter, water and energy, knows incoming flows of goods and people, optimizes every element entering its metabolism (energy, materials, but also intellectual resources and finance) and grows without producing harmful waste (greenhouse gases but also social disparity and unemployment).

At the same time, it enjoys emotional wellbeing: there’s nothing like happiness and optimism to cure any ailment. Furthermore, if it’s true that cities can be compared with biological ecosystems, then, as any other living organism, they can find survival and adaptation strategies in moments of deep crisis such as those we are experiencing.

This is the idea behind circular cities. Organisms that take less from the planet, make durable, shareable, repairable goods, and transform waste and pollutants into resources and jobs. This means re-thinking cities and the way we consume and produce in them.

If we take into consideration food, cities are the main places where we consume it (but with very limited production). Circular cities aims to reduce food waste (creating food banks or supporting innovative restaurant that produce zero food waste or use leftover for delicious Michelin-starred dishes), use what is inevitably left to produce composts or other products (such as beer from unused bread, like Bread Beer in Como, Italy or biogas from brewery’s spent grains, like Bryggeri in Helsinki Finland) and pushing for local production (Milan’s Parco Sud has become the largest urban agricultural area in Europe) that uses compost from urban wastewater plants or food waste collection.

Circular cites focus also on shared mobility. Half of the CO2 produced from a vehicle comes from its construction. Then it sits idle for 95% of its lifetime. Shared mobility services, like ZipCar or Car2go and scooter and bike sharing, together with efficient and cool mass transportation are a must in a circular city. A key strategy to reduce materials and greenhouse gas emissions, the circular approach is about that: making money from services instead of materials.

Circular water management is also a necessity, especially in drought-prone or flood-prone urban areas: building innovative water management systems and wastewater plants are key to minimize water consumption and extract value from…well you know what. Today useful biogas and biomaterials can be obtained from sludge.

Buildings are another critical element of the circular city: they account for almost 40% of the 100 billion tons of material extracted yearly. «The built environment is a key element of cities», says Carol Lemmens, Global Advisory leader for Arup, a construction engineering firm. «But the built environment lags behind other industries, like car manufacturing, fashion or high-tech». Buildings need to be produced with sustainable and recycled materials, employing a special passport that makes it easier to dispose of parts and wreckage waste when the buildings need to be refurbished, demolished or dismantled. A new wave of circular architecture is needed today, where buildings become modular, made of sustainable renewable materials – like wood, a common feature of traditional American architecture – or made with steel and glass, built to be easily refurbished, unbuilt or transformed.

In Europe circular cities are leading the way, especially in the Netherlands, where over 400 organizations including businesses, trade unions, environmental organizations, and local governments, signed a letter of intent regarding a National Agreement on the Circular Economy. «Public bodies, companies, civil society organizations, schools, and universities have committed to making their efforts converge toward two concrete goals: cutting the use of raw materials by 50% and significantly reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 2030», says politician and former Environment Minister Stientje van Veldhoven.

One basic goal for circular cities is Municipal Waste Management. The EU aims to recycle at least 55% of municipal waste by 2025, the 65% by 2035. In a time of material scarcity recycled materials become a strategic asset.

The Circular economy in the US

While terms like circular economy or circular cities aren’t that popular yet in the US, the trend is growing. While the majority of waste is conferred to landfill, recycling is gaining ground almost everywhere. Large American corporations have started to notice the circular economy revolution taking place in Europe and China. Today Coca-Cola, Adidas, Google, Unilever and many others have bold circular economy policies and they are influencing other big corporations and medium enterprises.

Charlotte, the largest city in North Carolina is on route to become the first city in the United States to implement a circular economy strategy. Launched in 2018, the Circular Charlotte initiatives drew inspiration from a report commissioned by the city council, titled “Circular Charlotte: Towards a Zero Waste and Inclusive City”.

According to the report, only 11.5% of materials were being reused or recycled, and circular business strategies were completely absent. Today, the epicentre of the transformation is the Innovation Barn. Located at a former stable in Belmont, this 3,500-square-metre renovated barn represents the first phase of Circular Charlotte, aiming to redirect waste, create new economies, and, last but not least, reduce the amount of public money being spent on waste management every year.

Innovation Barn was created by the non-profit Envision Charlotte, Dutch consultancy Metabolic, and architecture and design company Progressive AE. The Barn contains co-working spaces for upcycling and recycling, a space for composting, and an aquaponic garden equipped with plants and catfish. There will also be an open-air brewery and a zero-waste restaurant to help foster a sense of connectedness with the community. “One of the things we are trying to do with the Innovation Barn is providing examples of ‘closed-circuit’ systems, such as aquaponic and hydroponic gardens,” explains Amy Aussieker, Executive Director of Envision Charlotte. “We are also trying to convince people to come here so we can educate them to think differently about the materials that are found within waste and the ways they could be reused. They might not be interested in aquaponic gardens, they might just want to have a beer. But they come here and see something new.”

Miami

Circularity is coming also to Miami. In late 2021 the first Circularity Assessment Protocol (CAP) was conducted in the area surrounding the Miami River, a primer for this protocol that mainly focused on waste as a potential resource.

It collected data to empower the city decision-making and to answer important questions such as how plastic is used and disposed of in Miami, what actions can change the way it is used, how circularity can be increased, and how this impacts what materials and items end up on the ground.

Rather than a broad assessment, the CAP focused on consumer plastics, primarily single-use plastics, with the goal of reducing any plastics that reach waterways and our ocean.

However, the challenge in the city is much bigger than that. Miami is a member of the Resilient Cities Network, with an appointed Chief Resilience Officer who oversees the city’s progress and partnership in a cohort of 100 cities around the world. Making its economy and real estate resilient to climate change is critical as much as it is to maintain asset value yearly. In both case a systemic circular approach can help to boost resilience, reinforce the urban fabric, modernize process and strengthen Miami’s tourism.

Increasing circularity for a city not only can help keep pollutants out of the environment, but can save the city money, increase community engagement and protect the biodversity.

Interesting hotspots for the circular economy are for example dynamic neighbourhoods like Wynwood, a centre for art, fashion, creative and sustainable enterprises.

Wynwood is dotted with CitiBike bike-share stations, several places to share workspace, sustainable food businesses, innovative community-based shared practices and many creative green firms.

The neighbourhood has also another big plus: it is extremely walkable and bikeable, a key feature to decarbonize the city and attract green talents. But more can be done, like supporting the development of repair-cafés and push for clothes and goods swapping events, opening cleantech incubators and pushing public administrators to adopt bold circular goals, such as a food waste target or a zero-waste goal by 2040.

Future real estate operations will have to take into account circular economy models in their buildings to increase their longevity and value. After all, the circular economy is as much about the environment as it is to boost wealth and new businesses, while becoming more resilient to supply-chain-shocks and external events.

We have to rethink the economy, starting from our cities, and protect our prosperity.

You may also like

Life on deck

Tommaso Sagnelli, 28 year old Italian takes a life changing decision: quit his job, buy a boat and l

From Gaudí to Bofill

What Catalan architects can teach us about sustainability.

No Man is an Island

No man is an island, but even when he is, and lives happily, it means that he distanced himself from

Post a comment